The South Mountain Restoration Center began in 1901 with the construction of a single shack in the mountains of Mont Alto, Pennsylvania. Over the last one hundred years, the campus treated thousands of people for tuberculosis, mental illness and provided general care for the elderly. What began as a forestry camp, morphed into the White Pine Camp, the Mont Alto Sanatorium, the South Mountain Sanatorium, the Samuel G. Dixon State Hospital, the South Mountain Geriatric Center and finally, the South Mountain Restoration Center.

Mont Alto, PA: The Beginning

The town of Mont Alto, in Pennsylvania, began to support settlers in the 1760's, but it wasn't until the 1840's that the township expanded to include rolling mills, flouring mills, distilleries, a furnace and the first post office, which later served the center for a number of years. The Mont Alto Iron Works was established by Daniel and Samuel Hughes in the early 1800's and employed 500 local residents into the late 1800's. In 1872, Iron Works began paving a ten mile railroad as a means to transport coal to the iron furnace on the hill, the driving force behind the South Mountain and Mont Alto area.

In 1901, when Dr. Joseph Trimble Rothrock, the father of the forestry movement in Pennsylvania, took a group of locals to the mountains of Mont Alto to camp, one camper with asthma received great relief from the fresh mountain air, which led to the construction of a single mountain shack where he could seek solace. It's not likely Rothrock's intentions were to create a sanatorium, but the sanatorium developed from that single shack.

Dr. Joseph Trimble Rothrock

Dr. Joseph Rothrock was born in 1839. He attended public school for a few years, but due to poor health, he was taken out of school by his father and put to work on a local farm. He attended Harvard University until the Civil War broke out, when he was drafted. After being severely injured during battle, he was discharged and returned to Harvard. He graduated with a B.S. in Science and Botany, then moved on to finish Medical School at the University of Pennsylvania where he graduated in 1867.

Rothrock praciticed medicine throughout Pennsylvania for a number of years and in the late 1880's became President of the Pennsylvania Forestry Association. In 1904, he resigned due to poor health. One source claims that Dr. Rothrock also experienced "lung trouble" and suffered from tuberculosis, but in the early 1900's scientists were just beginning to learn the nature of such diseases.

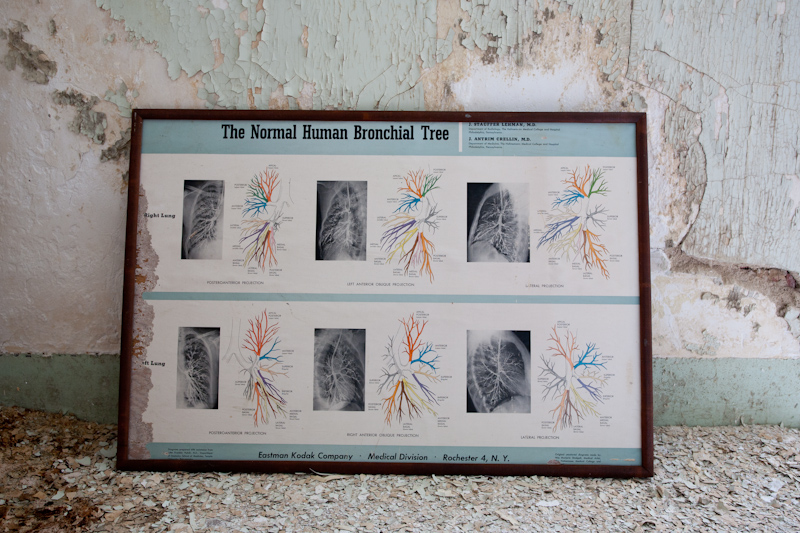

The History of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis in the nineteenth century was known as the "the white plague." Bovine tuberculosis, which was transfered to humans via cow's milk, would attack the bones, possibly leaving a patient crippled. Pulmonary tuberculosis, an airborne form, attacked the lungs and an infected person could spread the disease each time they coughed or spoke. At the time, the disease was difficult to treat since most patients would not see a doctor if they were experiencing symptoms (cough, lethargy, decline in health or pain in the chest) but most of the time, those who were infected wouldn't immediately exhibit any symptoms.

An infected patient experiencing the horrors of the disease would lose their appetite, cough severely, run a fever and have difficulty breathing. As the disease progressed towards the final stages, the body would waste away and the lung tissue would break up and be coughed up. The result was hollow faces with recessed eyes and shriveled bodies.

In 1882 Robert Kroch discovered the tubercle bacillus strain, which put a whole new spin on the treatment of the disease. After his discovery, the thought was that tuberculosis was preventable and curable. Most doctors treated patients by prescribing a change of location, fresh air, rest and excersise. This caused patients to be removed from their homes, where they could possibly infect others, and placed in a Sanatorium.

White Pine Camp: The Early Sanatorium (1901-1907)

Several additional shacks were built on the sanatorium campus over the next few years, due to private donations, and a few years later, Rothrock's camp received state funding. Construction began on an office building, water system and six cottages. Additionally, the funding helped furnish each cabin with beds, a kerosene lantern and woodstove.

In 1905, Rothrock started his own private sanatorium known as the Mountain Side Sanatorium, but only two short years later, he sold the property as he had no real intention to lead the fight against tuberculosis. At that time, the adjacent White Pine Camp housed 30 patients who paid one dollar per day for treatment, which was based on a balanced diet, fresh air and a careful balance of rest and excersise.

The Mont Alto Sanatorium (1907-1918)

"Dixon Cottages" at the Mont Alto Sanatorium.

Until now, the camp belonged to the Department of Forestry, but an act of legislature in 1907 allowed the transfer of the camp to the Department of Health. Additionally, $600,000 was appropriated to the camp, now known as the Mont Alto Sanatorium. This was the mark of a major effort to combat tuberculosis, as declared by Dr. Samuel G Dixon, Commissioner of Health.

In the first five years, the patient consensus grew from 30 to nearly 1,000. Due to the quickly growing population, a total of fifty-six "Dixon Cottages" were built to aid in the treatment of tuberculosis. The corners of the twenty six foot square cabins were aligned to the compass to allow an equal amount of light into each of the four rooms.

South Mountain Sanatorium (1918-1956)

In 1920, a second infirmary was built and eventually became the sanatorium's first children's hospital, otherwise known as a preventorium. In these days, children were extremely susceptible to tuberculosis and were sent to the preventorium for a few reasons. Some were malnourished and underweight, while some had actually been exposed to the disease. By sending these children to South Mountain, it was believed the full development of the disease would be prevented.

Shortly after the hospital opened, a tuberculosis training school for nurses opened on the campus. A nurse received training for two years and would spend time within various parts of the sanatorium as part of the program. Most of the nurses who worked at the sanatorium were recovered patients who were less uncomfortable handling those infecte with the disease.

Construction on the campus continued into the 1930's. A new wing was added to the preventorium, containing rooms for crippled children, classrooms and an auditorium. The preventorium and Nurse Homes closed in 1940 and were demolished shortly thereafter. Between 1938 and 1940, construction began on Units 1, 2 and 3 as well as a Nurse's Home and dining hall that still stand today. Unit 1 housed the most critical patients and contained operating suites, offices, kitchen, dining room, morgue and autopsy room, two movie theatres, an auditorium and bedside headsets for the patients.

The new four story Unit 2, Children's Preventorium, was designed by Morton Keast of Philadelphia and built by John McShain Inc. The central pavillion contained two wings, two indoor pools designed for tuberculosis patients, a library, four classrooms, excersise rooms, singe patient rooms, wards, an auditorium, lounges and a complete single family home for rehabilitation.

Exterior of fourth floor single-family rehabilitation house.

Living room of rehabilitation house.

Boys and girls remained separate at all times in the sanatorium. The first floor of the preventorium was designed as a boys floor, with nurse's stations, while the second floor housed the girls. A typical day for a child at South Mountain would have started at 7:00am when they woke and received breakfast and then played indoors until 10:00am. Afterwards, they would drink milk from the wagon, have lunch and rest in bed for several hours. No talking or movement was allowed during this time. At 3:00pm, they would again line up for milk and shortly after, they would sit down for supper. Games were played inside the wards until 7:00pm and at that point, the children listened to the radio for an hour before 'lights out' at 8:00pm.

The lobby of Unit 2.

The children admitted to the South Mountain preventorium who had not yet developed tuberculosis depended on good air, rest, moderate excersise and good food, which was thought to be six raw eggs and three quarts of milk per day. The patients also underwent a number of treatments and procedures, including heliotherapy. This process would help build up their resistance to sunlight by exposing them to it gradually. If a patient had a more advanced disease, they might undergo surgery to help treat scar tissue build up in the lungs to make breathing easier. It was also common for Pneumothorax to be performed, a procedure which involved injecting air into the area around the lungs to help the lung collapse. A treatments such as this was not available to all patients, especially those with lung scar tissue.

In 1945, the treatment of tuberculosis changed when a new, effective antibiotic was discovered. Streptomycin was an antibiotic given via injection, but it was highly toxic, had a number of side effects and a few of the strains actually became resistant to the medicine. In 1952, isonazid proved to be even more effective, less toxic and a patient immediately became noninfectious. In the upcoming years, patients admitted to sanatoriums were now released in a matter of months or even treated in general hospitals.

Samuel G. Dixon State Hospital (1956-1968)

Though the campus was again renamed, not much changed at the facility. Adult patients continued to be regulated just like the children in Unit 2. Patients in Unit 1 were ranked on a scale of four Roman numerals, determining their health status. The Class I patients were forced to remain flat in bed for the solid twenty four hours a day, only sitting up for meals. Class II patients were bedridden and confined to a wheelchair when moving among the facility and they would bathe with the assistance of a doctor or nurse. Class III patients were "restricted" but engaged in a number of activities as permitted by their doctor. They were able to walk to treatment rooms and restrooms and would have solarium visiting rights to watch television. They also participated in church services and walked to the dining hall for one meal every day. Class IV patients experienced the most freedom. They were able to participate in all activities: making their bed, attending movies and religious services as well as spending all meals in the dining hall.

Patients in Unit 2 were free to sit on the lawn behind the unit, weather permitting, and even got the opportunity to visit Unit 1 on movie nights. These patients required a minimum of 4 hours rest per day, but were free to move about the campus as long as they checked in with their ward during designated times.

Patients in all of the units in the sanatorium followed strict rules. Their wardrobe consisted of pajamas and bathrobes. The men were required to shave once every two days, to avoid the collection of germs inside their facial hair. Smoking was permitted only with doctor's permission.

The healthier patients in the outer units were given two weeks out of the sanatorium, but never during the holidays, as that was flu outbreak time. Educational courses were given to children between the ages of six and eighteen, but adults wanting to finish their high school diploma could also take these classes. Parents were allowed to visit their children in the Preventorium every other Saturday.

In 1961, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania still ran four tuberculosis hospitals including the Samuel G. Dixon State Hospital, but by 1963, the other three had closed. This signified a positive improvement in the treatment of the disease.

South Mountain Geriatric Center (1965-1968)

The state mental system in Pennsylvania by the 1900's was reaching a critical point. On average, the state hospitals were above capacity and approximately one-third of the mental patients were over the age of sixty-five. Most of these geriatric patients, when discharged, moved into the mental hospitals, but the mental hospitals did not provide adequate care for their medical and nursing needs. In turn, this caused the waiting list for patients needing serious mental care to increase rapidly. In 1964, the state approved the measures needed to establish geriatric facilities to care for these patients. Besides the South Mountain Geriatric Center, only one other geriatric hospital was founded in Pennsylvania.

At South Mountain, the new residents of the Geriatric Center, who transferred from Torrance State Hospital, lived on the first second and third floors of Unit 2, the old Children's Preventorium. Within the first two years, over 575 patients were admitted to the Geriatric Facility. On average, the patients were placed in a room with five beds. Wards were not locked, so procedures were taken to prevent patients from wandering and becoming confused.

The Samuel G. Dixon Hospital continued to operate within the other buildings on the campus. Unit 2 remained solely designated as the Geriatric Facility, but tuberculosis patients slowly began moving to the other hospitals in Pittsburg and Philadelphia. In 1972, the whole campus was devoted to Geriatrics, despite a long battle to re-open the tuberculosis hospital.

Third floor salon in Unit 2.

A typical patient room. This one contained 3 beds.

South Mountain Restoration Center (1968-Present)

In 1968, the Office of Aging lowered the age limit required for admittance into a Geriatric Facility from sixty-five to twenty-one. At the time, the center's policy stated that in order to be admitted to South Mountain, the patient must currently reside in a state mental hospital or state school for mental retardation, preferably over the age of sixty-five, and require medical care, but not institutional care for psychosis or tuberculosis. The patient must not have a drug or alcohol addition or be a danger to themselves or others. Admission priority went to those who had a greater possibility of re-entering the community after rehabilitation.

However, daily life for the patients at the facility did not always revolve around rehabilitation. An area known as "Mohler Den," which resembled a social club, was set up in Unit 2 as a place where patients could socialize and play cards.

In the early 1970's, the patient count reached about 1,100, but less than a decade later, it dropped to 800. The reduction in patients caused the gradual closing of a number of buildings on the campus. In October 1985, Unit 2 closed due to a deteriorating roof.

Today, VisionQuest, a facility for troubled youth still operates where the first preventorium once stood. The South Mountain Restoration Center also continues to provide medital, nursing and rehabilitative care as well as placement services for those leaving the facility. The Center also prides itself on creating a high level of functionining for those patients unable to return to society.

"For my friend Rita -- I guess I looked like this 26 years ago in 1944. The camera never lies. Youthfully yours, Bud"

Sources:

Yelinek, Kathryn. The History of South Mountain Restoration Center 1901-2001. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 2001.

South Mountain (Mt Alto Sanitorium). Clyde A. Laughlin. York College of Pennsylvania. <http://goose.ycp.edu/~ttaylor/laughlin/south_mountain.htm>